The real A.Q. Khan

By Nizamuddin Siddiqui

What motivated the father of Pakistan’s nuclear bomb — wealth or a higher calling? That’s the tough question this veteran reporter seeks to reveal

OPINION, May 30, 2025

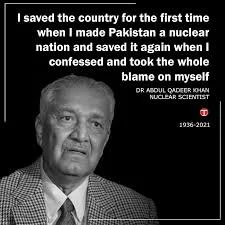

WAS Dr Abdul Qadeer Khan the greatest scientist produced by Pakistan? Certainly not. Was he a great engineer? Maybe, maybe not. However, what one knows for sure after closely following his long and eventful innings is that he was everything the nation needed him to be — an astute planner, a knowledgeable technologist, a strict administrator, an eloquent spokesperson for the cause, and even a wily worker of the ‘import-export business’ when required. To be sure, whatever he did was for the only cause he espoused all his life, acquisition of the one technology that could make the country’s defence insurmountable.

The fame and adulation that he enjoyed in the process, particularly in the 80s and the 90s, was simply unprecedented. Tall, a bit dark and handsome, the part of a national hero suited him. He came to be regarded as the no-nonsense professional who would get the job done. That’s why much before the nuclear explosions in Chagai confirmed that Pakistan had indeed mastered the coveted technology, most Pakistanis in the know of key developments were sanguine that the Rubicon would easily be crossed.

Then came 1998, the year when India tested its nuclear devices for the second time at Pokhran, Rajasthan. Some Indian leaders followed up these successful tests with bluster and hyperbole, one of them suggesting that New Delhi had finally called off Islamabad’s ‘nuclear bluff’. Almost simultaneously, there began in Islamabad a behind-the-scenes tug of war between two rival organisations — Dr A.Q. Khan’s laboratories (of Kahuta fame) and the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) — for the government’s nod to carry out the crucial retaliatory tests. Even though it was widely known that Dr Khan’s laboratories specialised in uranium enrichment only, they were so confident of their technical prowess that they wanted to supervise everything from enrichment to bomb-making to testing. This apparently did not go down well with the staff and supporters of PAEC, who mounted a campaign of sorts against the mighty Khan.

As it turned out, the Nawaz Sharif government asked PAEC and the Khan Research Laboratories to jointly carry out the tests. The tests, to the dismay of Pakistan’s enemies, proved to be successful. It was surely a watershed moment vis-a-vis Pakistan’s defence capabilities, but some of Dr Khan’s detractors were more happy that a drive to undermine the hero had finally been opened.

In 2003-04, his critics got hold of a lot of ammunition for unloading on him after it was alleged by some leading countries that Pakistan was involved in the leaking of designs of P1 centrifuges to such rivals of the US as Iran and Libya. In the eyes of Dr Khan’s detractors at home and abroad the case against him was settled the moment he appeared on national television and “confessed to those crimes”. Not only did they accuse ‘Mohsin-e-Pakistan’ of putting national interest in jeopardy by indulging in nuclear proliferation but also assailed him for doing so in order to mint money. It was a depressing episode for the admirers and supporters of Dr Khan who felt like kicking themselves for believing in him in an age when corruption and self-interest often prevail over such “narrow and hollow considerations” as patriotism and the national cause.

Face to face with a legend

One had interviewed him twice for daily Dawn and after the first of those sittings Dr Khan had sent over four signed books about his life and work. After his passing I began to read these books anew, looking for answers to the extremely difficult questions raised about him during his lifetime. I now feel that I have found answers to some of those tough questions in a book that comprises Dr Khan’s own articles about his worldview. (These articles are based on the speeches that he made and the papers he presented at various official events.)

On page number 174 of this book titled Dr A.Q. Khan on Science and Education, which was published back in 1997 by the Sang-e-Meel Publications, Lahore, he writes: “It is an open secret that fuel for the Indian Tarapur reactor was supplied by the USA till 1983 and, after that, by France, the same country which in 1976 backed out from an agreement to provide a reprocessing plant to Pakistan. Iran’s nuclear programme is also a target for a vicious campaign unleashed by the West despite the fact that it is signatory to the NPT (Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons) and, as a top official of the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) recently confirmed, no violation of the treaty has ever been reported. A top US official (was) quoted in the papers to have justified the pressure applied on Iran on the basis of apprehensions that Iran might opt for using its programme to develop nuclear weapons. The Muslim countries are being punished for supposed intentions.”

He goes on to write: “Pakistan, Egypt, Turkey, Algeria, Iran and Libya are the Muslim countries identified to have broad-based nuclear research programmes. Another Muslim country accused (of having stepped) onto this prohibited path was Iraq, whose nuclear installations were destroyed by two Israeli air attacks, an incident which caused little concern among the self-appointed custodians of international law. What Israel has been doing does not bother the West a little bit. South Africa also made nuclear weapons but the West did not take any action against it.”

The opening paragraph of this chapter, entitled ‘Restricted areas of science and technology and ways to develop such technologies in the Muslim World’, the father of Pakistan’s nuclear bomb says: “Science and technology is not the exclusive domain of a race or people. The very word ‘restricted’ reflects the self-assumed monopoly of the West over certain branches of science, and especially, its efforts to curtail the development of the Muslim World which the western powers unjustifiably see as a potential threat to their monopoly. Development made by certain Muslim states in the restricted technologies does not trickle down to others because of international pressure and lack of coordination and cooperation among the Muslim countries. The achievements of the Muslim scientists working in their own countries do not create a cumulative effect on the overall scientific and technological progress of the Muslim World because of the absence of an efficient and coherent mechanism of technologies developed by them. Thus, scientific and technological development in the Muslim World is visible in patches, not in the form of continuous, cumulative pattern.” (Page 169)

Dr Khan goes on to declare: “As most of the restricted areas of S&T are directly or indirectly related to defence products, I would like to propose that the defence research and development (DR&D) institutions and industries of the Muslim countries are engaged in joint defence production and military cooperation at the bilateral level….”

It’s obvious from the above assertions — made by Dr Khan himself in writing much before the ugly episode of 2003 — that international efforts to deprive Muslim countries of nuclear and missile technologies deeply hurt him. (One gets the sense that he actually felt offended by them.) He yearned to correct the wrongs.

So what he was labouring under was a higher calling, a far more important cause, than a mere craving to earn extra money as quickly as possible. The fact that soon after India had tested its first nuclear device in 1974 at Pokhran he contacted Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of his own accord and offered to help the nation deal with the situation lends credence to this view.

It’s noteworthy also that when Mr Bhutto asked him to return to the homeland, Dr Khan readily followed his instructions. He was leading a comfortable life in Europe at the time and was married to a western lady and yet he chose to move to Pakistan.